![]()

By J. Hoberman

October 21, 2016

In late 1970, Alejandro Jodorowsky’s druggy, mystical western “El Topo” opened at the Elgin Theater in New York with no more fanfare than a small notice in The Village Voice. The film was to be screened only at midnight, according to the ad, because it was “too heavy to be shown any other way.”

A new outré cinema was born: The violent “El Topo” established the template for subsequent midnight blockbusters, like John Waters’s shockingly crude “Pink Flamingos” (1972) and David Lynch’s fantastically weird “Eraserhead” (1977). Had the Japanese animator Eiichi Yamamoto’s psychedelic, sexually explicit “Belladonna of Sadness” (1973) opened at midnight, it, too, might have entered the cult pantheon.

As it was, Mr. Yamamoto’s film was a commercial failure in Japan and, despite a screening at the 1973 Berlin International Film Festival, took more than 40 years to arrive in the United States; last spring, newly restored, it enjoyed brief theatrical runs in New York and Los Angeles and is now out on Blu-ray from Cineliciouspics. It’s also available for streaming from Amazon Video.

A product of countercultural magical thinking, “Belladonna” was inspired by “La Sorcière,” the 19th-century French historian Jules Michelet’s examination of the medieval witch mania as a rebellion, led mainly by women, against the feudal order and the Catholic Church. The movie is also something of a revolt — against constraints of good taste as well as conventional animation.

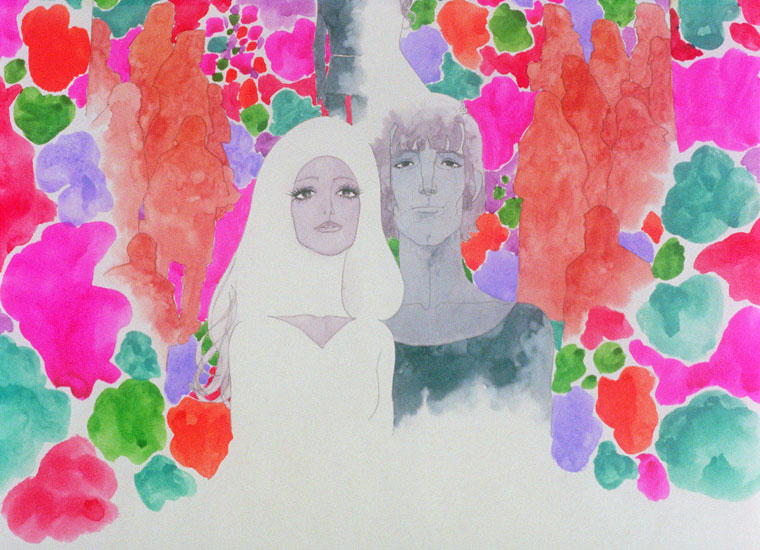

Mr. Yamamoto, an associate of Osamu Tezuka, the founding father of contemporary manga and anime, employs a variety of styles. Much of “Belladonna” unfurls like a scroll, with Mr. Yamamoto using forms of conventional cel animation and the “limited animation” associated with his television series like “Astro Boy” and “Kimba the White Lion,” panning across or zooming in on static drawings.

With its flat patterns, sinuous lines and entwining forms, “Belladonna” refracts traditional Japanese graphic art through the prism of the Art Nouveau or Vienna Secession, two movements that were in some ways inspired by Japanese woodcuts. It also echoes the candy-colored psychedelia of the Beatles’ “Yellow Submarine” (1968), the prurient French science-fiction comic book Barbarella and the late-1960s poster art associated with the San Francisco rock scene. “Belladonna” is eye-popping and ear-catching. The score, by the jazz pianist Masahiko Sato, might be characterized as “acid twang” in its evocation of Pink Floyd and Ennio Morricone.

The movie’s look is as flowery as its title. Still, the delicate lines and pastel splashes of color are frequently at odds with a sexual violence at once explicit and powerfully abstract. Reviewing “Belladonna” in The New York Times last May, Glenn Kenny called the movie “compulsively watchable, even at its most disturbing.”

The protagonist, Jeanne, an initially shy, sad-eyed damsel who might have been the subject of a song by a hippie troubadour, is raped on her wedding day by the demonic local lord — and then again, repeatedly, by Satan himself. (The Devil speaks with the deep, seductive voice of Tatsuya Nakadai, an actor best known in the West for his samurai roles, and appears in various guises, including that of a disembodied penis.)

Part abused victim, part avenging riot grrrl, Jeanne takes up witchcraft, ultimately becoming so powerful that the feudal lord who first violated her tries to enlist her as his ally. She refuses — or rather, she makes a demand he cannot satisfy — and is thus arrested and martyred at the stake. A brief coda added for an expurgated but still unsuccessful Japanese release flashes forward to the French Revolution, identifying Jeanne with Eugène Delacroix’s 1830 painting “Liberty Leading the People.”

“Belladonna of Sadness” — described in a Japanese trailer included as a Blu-ray extra as “a typical Romanesque anime of intense eroticism and lyrical sorrow” — is organically outré.